“We are being lied to.”

So begins the 2023 essay by the tech investor and entrepreneur Mark Andreessen published as the Techno-Optimist Manifesto [1]. Andreessen goes on to say why, in his opinion, we are being lied to:

“We are told that technology takes our jobs, reduces our wages, increases inequality, threatens our health, ruins the environment, degrades our society, corrupts our children, impairs our humanity, threatens our future, and is ever on the verge of ruining everything.”

In the remainder of his manifesto Andreessen attempts to debunk this and the other “lies” he believes we are being told about technology. Techno-Optimists, he says, believe that societies are like sharks and must either keep moving forward technologically, or die. Andreessen has a vested interest in this being so. His venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz (aka a16z), as it says on their website, “backs bold entrepreneurs building the future through technology”. In short, a16z lives or dies through the investments it makes and for as many of these investments to be a success. If the a16z shark stops making good investments to move forward, it too dies.

This post is also a manifesto, but one that takes a more pragmatic as well as a more realistic approach, to the impact that technology, especially digital technology, is going to have on human-kind and on the planet we inhabit. If ever there was a time for a more balanced and rational approach to how we should be thinking about, as well as using, technology then that time must surely be now.

When talking about a subject as important as the impact technology is having on societal development it’s very easy, and somewhat trite, to use cliches like “humanity is at a cross-roads”, we are approaching a “tipping point” or “this time it is different.” In this and subsequent posts I will try to set out the reasons not just why humans are at a point in their evolution where we face a perfect storm that may well change the lives of everyone on the planet but how we might mitigate against the risks the current wave of technology will bring.

I don’t want this to be just another set of posts that list an endless set of problems with no apparent solutions and leaves the reader with a very real sense that we are all doomed. I want to point out what issues we face but in a way that explains how we could avoid the threats to our existence without accepting uncritically the optimism that is peddled in people like Andreessen’s writings and work. This series of posts will also be a manifesto, but hopefully one that is based on a more sensible approach to how we might develop and deploy current and future technologies without destroying human dignity or the planet we all inhabit.

Hence technorealism.

Technorealism was introduced by Douglas Rushkoff in 1998 [2]. Its stated aim was to “forge a middle ground between techno-utopianism and techno-Luddism”. A technorealist (i.e. someone who follows the technorealism approach) believes that technologies should be assessed for their social, political, economic and cultural implications before they are implemented in a wholesale and unregulated way after which, it is often too late to limit or control their widespread and sometimes catastrophic impact.

Technorealism, as originally described by Rushkoff, suggested a number of principles for how we might adopt a more commonsensical, approach to living with technology. Reading these today, they seem a little dated and too focussed on what were seen as the prevailing technologies and concerns of the time. This and following posts is an attempt to update the original technorealist principles but can also be read as a response to Andreessen’s 2023 essay.

I will be using the term ‘technology’ in its broadest form. However, because of my background (as a software engineer) and because of the particular impact computers are having on the world right now, the main focus will be on digital technology.

Broadly speaking we can think of technology in two ways [3]. Firstly as a means to fulfil a human purpose or need. Sometimes this purpose is very specific — the purpose of a hydroelectric dam is to generate power by harnessing and controlling water for example. Other times the purpose may be less well defined and both multiple and changing. A computer is a good example of this type of technology. As a means, a technology may be a process or a device. Oil refining is a process whereas an oil refinery is a (large scale) device to enact the process of refining oil.

The second way we can think about technology is as an assembly of practices and components. These can be very broad (computer technology) or more narrow (artificial intelligence).

I will use the term technology interchangeably to mean either a means to fulfil a human need or as a process or a device.

Technology has always been a force for both good and for evil. The technology that allows us to enrich uranium to increase the percentage of the isotope U-235, which is responsible for nuclear fission, can enable uranium to be deployed both in a nuclear power station as well as an atom bomb. Up until this point in human history technology has largely been in our control and has been our gift to use as we see fit — whether to our advantage or our detriment. So what is different now?

In his book The Coming Wave [4] the co-founder of DeepMind and Inflection.AI, Mustafa Suleyman, describes how the triplet of technologies: artificial intelligence, quantum computing and synthetic biology could lead to one of two possible (and equally undesirable) outcomes:

- A surveillance state (which China is currently building and exporting).

- An eventual catastrophe born of runaway development.

In Suleyman’s view these technologies could enable a radical proliferation of power like no other in human history. The reasons why this might happen, and why it really could be “different this time” are:

- Asymmetry — the potential imbalances or disparities caused by artificial intelligence systems being able to transfer extreme power from state to individual actors.

- Exponentiality — the phenomenon where the capabilities of AI systems, such as processing power, data storage, or problem-solving ability, increase at an accelerating pace over time. This rapid growth is often driven by breakthroughs in algorithms, hardware, and the availability of large datasets.

- Generality — the ability of an artificial intelligence system to apply their knowledge, skills, or capabilities across a wide range of tasks or domains.

- Autonomy — the ability of an artificial intelligence system or agent to operate and make decisions independently, without direct human intervention.

- Technological Hegemony — the malignant concentrations of power that inhibit innovation in the public interest, distort our information systems, and threaten our national security.

- Techno-paralysis — the state of being overwhelmed or paralysed by the rapid pace of technological change caused by technology systems.

This is a formidable list of wicked problems which could easily make you cry out in despair whilst thinking what can I possibly do when faced with such issues and is it too late to do anything? Should we not just defer to the greater knowledge and wisdom of our technology overlords in Silicon Valley and Zhongguancun in Beijing (China’s innovation hub and home to nearly 9,000 high tech firms) and hope their optimism plays out?

Andreessen and the other patron saints of techno-optimism believe that any real world problem can be solved by technology and that the market economy is a “discovery machine” that will generate societal wealth for everything we need like basic research, social welfare programs, and national defence. I am not so sure. Can we not chart a different path? A path that could lead to a better, kinder, greener and more socially fair world whilst at the same time avoidng us sinking back to a pre-digital dark age which the Neo-Luddites may lead us to [5].

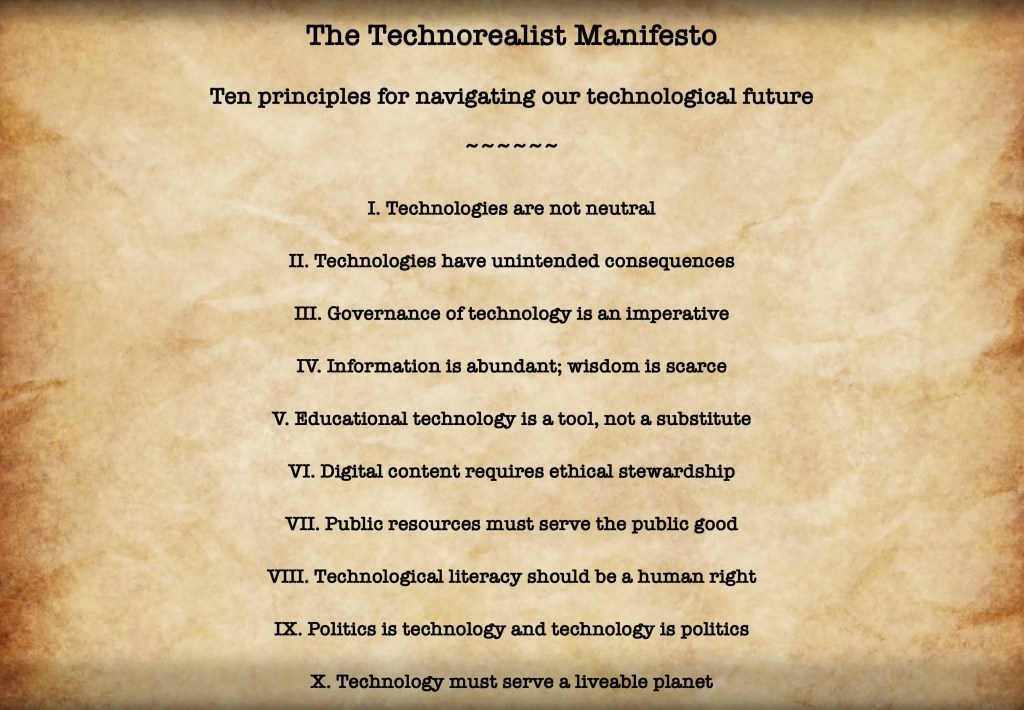

Here then are my ten principles on how we might navigate the dark and choppy technological waters ahead of us. Whilst these insights may not lead to the techno-Utopia envisaged by Andreessen and his acolytes, they might at least enable us to co-exist with, rather than be ruled by, our technology. This manifesto is meant as an act of resistance against what the Greek economist Yanis Varoufakis refers to as technofeudalism [6]. Technofeudalism is the post-capitalist ideology whereby our digital platforms and the data that resides in them have become the land controlled by a few tech giants and the leaders who own and run those companies.

My hope is that as far as possible these principles are future proof (a brave claim, I know) to whatever digital technologies may come along.

I. Technologies are not neutral

All technologies are influenced by the intentions, assumptions and biases of their creators [7]. Technology encourages certain behaviours, habits, and interactions while disregarding or ignoring others. Technorealists, whether as creators or users, must critically assess the biases contained in a technology to ensure they align with their ethical values.

II. Technologies have unintended consequences

While early 21st century technologies like artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, and blockchain undoubtedly have transformative potential, they do not not solve societal issues without having undesirable or unexpected outcomes. For every advancement, there are often downsides such as increased surveillance, more inequality, loss of privacy or spread of misinformation. These unintended consequences must be identified and managed responsibly [8].

III. Governance of technology is an imperative

If technologies are prone to unintended consequences then it follows they require circumspect regulations that balance innovation with the public good. Ideally governments, private organisations and citizens need to collaborate in setting standards that address privacy, ethical, security and data. Regulations must be established that balance achieving equitableness and transparency without crushing creativity and innovation.

IV. Information is abundant; wisdom is scarce

Today’s technologies have the ability to collect and analyze information on an unimaginable scale. So much so that it has far exceeded our ability to derive meaning from it. Converting information (and data) into understanding and knowledge requires rational thinking, contextual understanding, and a moral responsibility to the truth.

V. Educational technology is a tool, not a substitute

Though technology may enrich learning experiences it should not be allowed to replace the human elements of education. Empathy, mentorship, adaptability to individual student needs and real, physical interactions must always prevail. Investments in supportive technology should focus on giving teachers and learners tools that enhance, not replace, these essential tenets.

VI. Digital content requires ethical stewardship

Intellectual property laws must evolve to address new mediums while maintaining fair use and open access. Platform providers and technology developers must balance protecting rights whilst also cultivating creativity and collaboration across digital communities.

VII. Public resources must serve the public good

Online spaces should be public assets that prioritise educational, cultural and social benefits over those of profit, personal gain or political gerrymandering. Policymakers must ensure these resources are transparent and open.

VIII. Technological literacy should be a human right

Understanding how technology works and its impact on society is essential in the modern world. Citizens of all ages and social backgrounds should not just be provided with help in using technology but must also be allowed to actively engage with its design, ethical implications and how it is governed [8].

IX. Politics is technology and technology is politics

Every design choice made when developing a new technology, whether it be what data is collected or whose labour it might automate, potentially hands control to a third party which may or may not be a benign actor. Likewise, political decisions can influence the conditions in which technologies are developed and deployed. There is no such thing as ‘value-free innovation’ when algorithms are imbibed with ideology [9].

X. Technology must serve a liveable planet

There will be no technological progress if our planet is dead. Whether it be AI’s energy demands or the mining of rare earth elements to develop the latest hardware, every innovation carries ecological costs. Technology must not just be a tool for endless growth that scales fast and breaks things. It must be used to help repair the damage humankind has done to the planet. We need tools that support economic growth but not at the cost of ecological genoocide.

Technorealism isn’t meant to be a manifesto for or against technology. It is meant to be a call to reclaim our agency over it. The hope is that with these principles, we can foster innovations that serve democracy, dignity, and equity.

It is my intent that each of the principles established in this introductory post are fleshed out in more detail in subsequent pieces here on Medium and maybe, one day, be published in book form.

Please provide comments for improvement, ideas to extend this manifesto and, of course, constructive criticism.

References

- Andreessen, Mark, The Techno-Optimist Manfesto, 2023, https://a16z.com/the-techno-optimist-manifesto/.

- Rushkoff, Douglas, Technorealism, Published in *The New York Times* and *Guardian*, 1998, http://archive.rushkoff.com/publications/nyt_syndicate_guardian_of_london.html.

- Arthur, W. Brian, The Nature of Technology, p. 28, Penguin Books, 2009.

- Suleyman, Mustafa, The Coming Wave, Bodley Head, 2023.

- Glendinning, Chellis, Notes toward a Neo-Luddite Manifesto, 1990 https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/chellis-glendinning-notes-toward-a-neo-luddite-manifesto

- Varoufakis, Yanis, Technofeudalism — What Killed Capitalism, Bodley Head, 2033.

- Hare, Stephanie, Technology Is Not Neutral — A short guide to technology ethics, London Publishing Partnership, 2022.

- Postman, Neil, Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology, Vintage Books, 1993.

- Cadwalladr, Carole, This is what a digital coup looks like, TED, April 2025, https://www.ted.com/talks/carole_cadwalladr_this_is_what_a_digital_coup_looks_like

Leave a comment