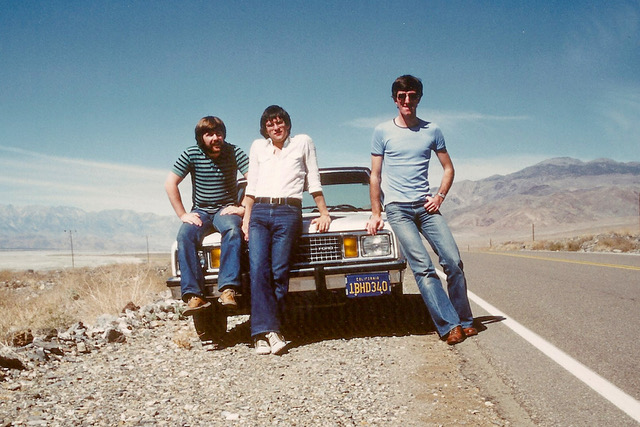

It was 1981, and I’d been in my first job for two years. I decided it was time to spend some of my newly earned salary, so two friends and I organised a three-week trip to the United States. We planned to spend part of it on a road trip in California. Here we are somewhere on CA-190 (I think), approaching Death Valley.

We started in San Francisco and ended up in Los Angeles. Our route took us through Yosemite, Death Valley, Las Vegas, the Hoover Dam, and the Grand Canyon — a distance of just under 1500 miles.

I lost touch with Kevan (in the middle), but Martin (on the left) and I remained lifelong friends. Martin moved to America in the mid-90s. We often talked, first by phone and then online, about getting together. Maybe we would do it when we had retired, and maybe we would undertake one of the great American road trips. Sadly, Martin died in 2018, so we will never do that together, but the appeal of such a road trip remains.

There are many roads in the US that qualify for supporting such an adventure. Route 66, which runs from Chicago to Los Angeles, is 2488 miles. Interstate 5 is the main north–south highway on the West Coast. It covers a distance of 1381 miles from Blaine in Washington state to the Mexican border in San Diego. Interstate 95 is the main north–south road on the East Coast. It runs from Miami, Florida, to the Houlton–Woodstock Border Crossing between the US and Canada, a distance of 1906 miles.

The mother of all road trips, though, must be the one along Interstate 80. This east–west transcontinental highway is one of the original routes of the Interstate Highway System, crossing the United States from San Francisco, California, to Teaneck, New Jersey. This route, if not the actual highway, also happens to be the one the three people I have been reading about would have at least partially travelled along.

Jack Kerouac, the writer; Robert Frank, the photographer and the singer-songwriter Bruce Springsteen all captured, in their own way, the uneasy truths of the American dream whilst taking numerous trips along this east-west route.

The work each of these artists created, how being ‘on the road’ influenced their art, and the ways in which they are connected have begun to fascinate me and reinvigorated my desire to take my own road trip.

The writer: Jack Kerouac and his book ‘On the Road’

The first draft of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road1 was written during a three-week typing frenzy in April of 1951. Kerouac believed that his verbal flow was interrupted when he changed paper at the end of a page. To avoid this, he taped together 12-foot lengths of drawing paper. These were cut to fit his typewriter, allowing him to type nonstop. The final version of On the Roadwas a 120-foot, single-spaced paragraph! The manuscript went through several revisions and was finally published in September 1957. The copy shown in the image is from the 2000 Penguin Classics edition. It features an image from Robert Frank’s The Americans on the front cover.

On the Road is an autobiographical novel. It describes four road journeys taken by the protagonist, ‘Sal Paradise’ (Kerouac). He travels with his friend ‘Dean Moriarty’ (the American writer Neal Cassady in real life). Kerouac populates On the Road with other well-known members of the literary subculture movement known as the Beat Generation. ‘Carlo Marx’ in the book is the poet and writer Allen Ginsberg. ‘Old Bull Lee’ is the writer and visual artist William Burroughs.

The road trips in Kerouac’s book consist of high-speed and chaotic races. They are manic sprints across the Midwest from New York to San Francisco and back again. The final journey extends to Mexico. Narrated by Sal, these trips involve endless ad-hoc meetings. He encounters all strata of 1940s American society. They are often fuelled by copious amounts of alcohol, drugs, and sex.

On the Road is a coming-of-age story for post-war America. Young men and women are discovering freedom for the first time. They are being liberated by long, straight roads, affordable automobiles, and cheap gas. More than anything, it highlights the diversity of the American Midwest. It also showcases the crazy dive bars, clubs, and music of 40’s America. Kerouac’s prose truly shines when he describes the music scene. He vividly portrays the various stopovers Sal and his gang make on their trips. Here’s Sal describing a jazz performance at a “sawdust saloon” in San Francisco.

“The tenorman jumped down from the platform and stood in the crowd, blowing around; his hat was over his eyes; somebody pushed it back for him. He just hauled back and stamped his foot and blew down a hoarse, baughing blast, and drew breath, and raised the horn and blew high, wide, and screaming in the air. Dean was directly in front of him with his face lowered to the bell of the horn, clapping his hands, pouring sweat on the man’s keys, and the man noticed and laughed in his horn a long quivering crazy laugh, and everybody else laughed and they rocked and rocked; and finally the tenorman decided to blow his top and crouched down and held a note in high C for a long time as everything else crashed along and the cries increased and I thought the cops would come swarming from the nearest precinct.”

In On the Road, Sal Paradise/Jack Kerouac and his buddies are creating their own version of the American Dream. They are living it out both literally and metaphorically at 100mph. They survived World War 2 in one piece, at least physically. Now, they are grabbing everything they can get from a new world. This world seems to offer them plenty.

Despite his hard living, Sal Paradise is a survivor. At the end of On the Road,we find him sitting on an old broken-down river pier where he is: “watching the long, long skies over New Jersey and sense all that raw land that rolls in one unbelievable huge bulge over to the West Coast…”.

Kerouac himself is less lucky. He died in 1969 at the age of 47. His cause of death was listed as an internal haemorrhage caused by cirrhosis, the result of long-term alcohol abuse.

The photographer: Robert Frank and his book ‘The Americans’

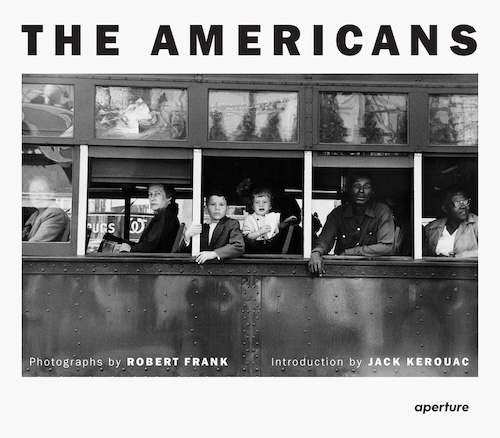

Robert Frank’s The Americans², with an introduction by Jack Kerouac, was first published in 1958. This was coincidentally the year I was born. Its origins are now well known, in photographic circles at least. Frank had obtained a fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation in 1955. This allowed him to travel across America. He photographed its people and places at all social levels. He went on several road trips between 1955 and 1956. During this time, he created 28,000 images. Only 83 of these were selected by him for this iconic book.

Looking at The Americans now, 66 years later, some of the images look almost amateurish in their composition (e.g. Parade — Hoboken, New Jersey) while others definitely deserve the label ‘iconic’ (e.g. U.S. 285, New Mexico). Yet looking more deeply at the book as a whole, you soon realise that its theme (i.e. American society and culture of the mid-fifties) is superbly captured. It does not matter that some of the images are blurred and grainy or composed in a way that makes you suspect they were ‘grabbed’ rather than composed. What matters is that they capture a way of life that was changing irrevocably.

This was America, post-Second World War. It was also a time in which the Cold War was underway, and the full horrors of the war in Vietnam were yet to unfold. The rampant commercialisation of Western society was only just beginning.

This was also a time of great racial divide. There were clear differences between parts of American society, which Frank captured so well. It was also before the huge issues of globalisation and neoliberalism had taken hold. The challenges of climate change, the Internet, and social media had not yet begun to dominate.

The Americans is a snapshot of a country that has now disappeared. In other ways, though, at least in part, it is still very much alive. Look at Assembly line — Detroit or Men’s room, railway station — Memphis, Tennessee or any of the numerous images of bars and cafes and you’ll understand what I mean. These are all scenes and places you’ll see today. Now, brand names and logos will be festooned everywhere. Yet, the people who populate these places will be no better off. They will not feel they have more meaningful lives than they did then.

Many of the people in Robert Frank’s photographs of 1950s America would now also be found in 2020s America. These individuals might be struggling to survive day-to-day. They may have lost their jobs to globalisation and struggle to pay their medical bills. What would a modern-day Robert Frank find? If he undertook that trip today, what stories and images would emerge? The 28,000 images that he took are probably uploaded to Instagram every few seconds today. We are overwhelmed with images like never before. Few of these images would be such a cohesive, intimate and intentionalset of photographs that Frank took, though.

In many ways, as Kerouac says in his introduction, Frank’s images are more poetry than photography:

“Robert Frank, Swiss, unobtrusive, nice, with that little camera that he raises and snaps with one hand he sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film, taking rank among the tragic poets of the world.”

The singer-songwriter: Bruce Springsteen and his album ‘Nebraska’

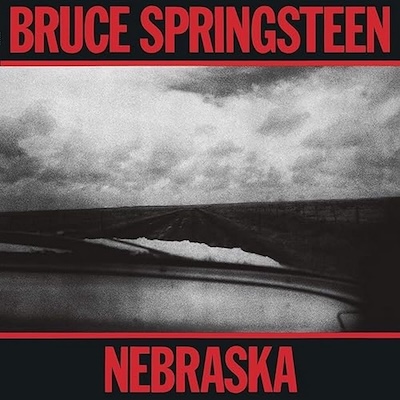

The creation of Bruce Springsteen’s album Nebraska³ is documented in Warren Zanes’ book Deliver Me from Nowhere4. (Also beautifully captured in the film of the same name starring Jeremy Allen White as ‘The Boss’).

The book chronicles the brief period in Springsteen’s life that began at the end of the River tour in September 1981 and continues until the release of Nebraska in September 1982. This was a pivotal time in Bruce’s life when he was on the brink of superstardom. Despite the expectations bearing down on him, he resisted making the next blockbuster album (that would be Born in the USA), choosing instead to focus on the raw and bleak songs that would ultimately become Nebraska. During this time, Bruce is struggling with issues of his own identity, wondering how he can live with himself if he is torn away from his roots. As he says in his autobiography Born to Run5:

“The distractions and seductions of fame and success as l’d seen them displayed felt dangerous to me and looked like fool’s gold. The newspapers and rock rags were constantly filled with tales of good lives that had lost focus and were stumblingly lived, all to keep the gods (and the people!) entertained and laughing. I yearned for something more elegant, more graceful and seemingly simpler.”

So, rather than indulging in the good life, Bruce moved into a rented house in Colts Neck, New Jersey, where he wrote and recorded all of the Nebraska songs (as well as a good part of what would become Born in the USA). As he says in the book Born to Run, “Nebraska began as an unknowing meditation on my childhood”.

Bruce wrote these songs very quickly and went on to record them himself in his bedroom (with the help of his guitar technician, Mike Batlan) on a TEAC 144 four-track cassette recorder without any of the production techniques most albums would go through. The songs on Nebraska were all based on experiences that came from his early years growing up in New Jersey.

Songs like “Mansion on the Hill”,

At night my daddy’d take me and we’d ride

through the streets of a town so silent and still

Park on a back road along the highway side

Look up at that mansion on the hill

and “My Father’s House”,

My father’s house shines hard and bright

stands like a beacon calling me in the night

Calling and calling so cold and alone

Shining cross this dark highway where our sins lie unatoned

He was also looking to write “black bedtime stories” music that “sounded good with the lights out”, which was “the opposite of rock music”. Songs like the title track “Nebraska” which is about a young man and his girlfriend who go on a killing spree through the badlands of Wyoming and end up being sentenced to death in the electric chair,

Sheriff, when the man pulls that switch, sir

and snaps my poor head back

You make sure my pretty baby

is sittin’ right there on my lap

Despite getting no publicity and having no tour to support it, Nebraska got good reviews and a very respectable chart positioning (it reached number 3 in the charts in October 1982). However, Bruce’s personal angst had still not been satiated, despite the album’s success. In the winter of 1982, Springsteen and his old friend Matt Delia packed up Bruce’s ’69 Ford XL and set off on a road trip to the Hollywood Hills and a cottage Springsteen had recently purchased.

Rather than taking a direct line from New Jersey to LA, the pair took some diversions south — first to visit Memphis, Tennessee, and then New Orleans — before heading west, crossing the Mississippi and on into Texas. At some point between Texas and California, they drive into a small town where a fair is taking place. A local band is playing, and the town’s inhabitants are dancing to the music. For some reason, this triggers something inside Springsteen, which he describes in Born to Run:

“From nowhere, a despair overcomes me; I feel an envy of these men and women and their late-summer ritual, the small pleasures that bind them and this town together… Right now, all I can think of is that I want to be amongst them, of them, and I know I can’t. I can only watch. That’s what I do. I watch… and I record. I do not engage, and if and when I do, my terms are so stringent, they suck the lifeblood and possibility out of any good thing, any real thing, I might have.”

Springsteen eventually arrives at his new home in LA, but by this time, he is deep into a depression. Luckily, with help from his manager, Jon Landau and long periods of therapy over many years, Bruce learns how to control his feelings even though, as he says, “in all psychological wars, it’s never over”.

So, apart from the very obvious road trips themselves, what connects these three artists?

For each, the road was a form of pilgrimage

For Kerouac’s Sal Paradise, he was discovering a new version of America. His discovery of the post-war American Dream was a revelation not just to Kerouac/Paradise but also, I suspect, to readers of the book On the Road.

Robert Frank, using a Guggenheim grant, zigzags across the States, making 28,000 photographs, a small selection of which become The Americans, a visual journey through 1950s America that Kerouac captures in words.

Springsteen’s journey from New Jersey to the Hollywood Hills, detouring through Memphis and New Orleans, may have started as a musical pilgrimage but turned into a reckoning with his own life and career.

As a nice link between the three artists, the Penguin Classics edition, of On the Road, uses one of Frank’s photographs on the cover, and Kerouac writes the introduction to The Americans. We also know that Springsteen was influenced by Kerouac’s book (from his autobiography5 and radio show6) and owns several copies of The Americans4.

Their style is deliberately stripped down and rough- edged

Kerouac typed his first draft using an old Underwood Portable onto a 120‑foot scroll to maintain a “verbal flow” that matched the chaotic energy of his road trips.

Frank’s pictures, taken on a Leica III Series, are blurred and grainy and seem more ‘grabbed’ than composed. Together, though they form an engaging and “poetic” portrait of a changing country.

Springsteen records Nebraska at home on a TEAC 144 four‑track, creating raw stories of working-class lives that sound, deliberately, the “opposite of rock music.”

Their focus was on ‘ordinary’ Americans

Setting aside the drinking and the drugs, On the Road is really about the numerous encounters the protagonists have with ‘ordinary American folk’. These are not film stars or business moguls but regular people trying to survive in a rapidly changing and expanding world who frequent the bars and clubs spread across the continent.

Robert Frank meets those same people and takes photographs of them. Everyone, from a candy store in New York City to assembly lines in Detroit or a car accident on US 66 in Arizona, becomes a subject for Frank’s Leica.

The people Bruce Springsteen writes and sings about in Nebraska are the working‑class people that he grew up with and the ones living in small towns on the margins rather than the centres of business, finance and the media.

All are observers, not participants

Kerouac’s Sal Paradise, whilst playing witness at frenzied jazz sessions, is ultimately the storyteller who will later shape what he observes into a novel.

Frank is the voyeur, the outsider whose Leica “sucked a sad poem right out of America,” turning him into one of the “tragic poets of the world.”

Springsteen recognises himself as someone who will “watch… and record” rather than truly join the dancers at the fair. As he says, “It’s here, in this little river town, that my life as an observer, an actor staying cautiously and safely out of the emotional fray, away from the consequences, the normal messiness of living and loving, reveals its cost to me”.

Ultimately, the road’s perceived freedom is illusory

Kerouac’s characters, as well as the man himself, appear to be chasing freedom but burn out physically and emotionally.

Frank’s America, although outwardly mobile, is socially frozen. He photographs people divided by race, class, and labour who “will be no better off” despite the rising affluence of a more consumerist society.

Springsteen discovers that escape does not resolve inner conflict but instead, on the brink of superstardom, fears fame as “fool’s gold”.

Each of these artists had very different reasons for undertaking their trips. What have I learnt personally from studying their art and trying to understand what motivated them?

It is simply this, sometimes in life the need to escape from the everyday can overwhelm us. The freedom we think we might achieve, though seemingly seductive, is ultimately likely to be illusory. When we return, or arrive, it is doubtful those problems will have gone away or will finally catch up with us. The brief encounters we are likely to have, and the experiences we might gain, may be gratifying in the short term but are unlikely to be life-changing. They may well be the “fool’s gold” that Springsteen speaks of and which may be best left unmined and untouched.

I realise that at my age, embarking on the kind of long trips these young men did would ultimately be fruitless, and anyway, Trump’s America is hardly an inviting place to visit right now. It’s time to put to rest my youthful fantasy and concentrate instead on my writing and photography closer to home.

References

- Kerouac, Jack, On the Road, Penguin Classics, 2000 Edition

- Frank, Robert, The Americans, Aperture, 2024 Edition

- Springsteen, Bruce, Nebraska, Columbia, 1982

- Zanes, Warren, Deliver Me from Nowhere — The Making of Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska, Crown, 2025

- Springsteen, Bruce, Born to Run, Simon & Schuster, 2016

- Lustig, Jau, Springsteen takes listeners for a ride on 13th SiriusXM DJ show, October 7, 2020

Leave a comment